A Gift to Enable Life

by the Rt. Rev. Dr. Arthur J. Freeman

Theology is often regarded as purely an academic enterprise for professional theologians who seek to understand the mysteries of God. While deeply thankful for those who have assumed this vocation and have published numerous volumes on theology and the related concern for Scripture, those who pursue different ways of earning a living in their life process hold profound theological questions in their minds and hearts: Where is God? How can I know what she or he is like? Where will I discover this? Who am I? What is the role of Jesus? What do I do with Scripture which at times seems so helpful and yet confusing? How do I live with the strange forces I find in life and in myself? Does anything happen when I pray? What happened to my father when he died? Are there values for living and making decisions? Can the church deliver what it seems to promise?

To think theologically is not merely to raise questions about God, but to bring God to life, to allow the resources of God and church to question, engage, encourage, inspire and inform our lives. This living out of theology and reflecting upon it and life, at the same time transforms the quality of human existence and makes of every lay woman and man who ponders life a theologian. This was very much Zinzendorf’s understanding of theology and it is interesting that he developed some lay persons who were quite competent in theology. Zinzendorf’s closest thing to a book on theological topics was his Twenty-one Discourses on the Augsburg Confession where he followed the articles of the Lutheran Confession. Though he had passed theological exams before Lutheran faculties, he chose sermons as his primary literary theological product – volumes of them in which his theology was expressed and shared.

In recent years there has been recognition that theology always has a context in life: it is thought out somewhere, by some one, in some culture, in persons’ lives with particular questions. Thus it does not surprise us to meet theologies which each have their unique expression: feminine, liberation, Caribbean, Afro-American. It does not surprise us to find in Scripture four differing presentations of Jesus or to have Paul tell us that he preached in different words to Jew and Greek. Nor does it surprise us to have different theological traditions with long histories of research and discovery. The Moravian theological tradition is over 500 years old, tracing back to 1457, and represents some decisive shifts: the initial attempt to simply follow Jesus as stated in the Sermon on the Mount; the later recognition that the thought of the church had to be more related to the world; the development in which Moravian theology affirmed the Essential of relationship with God, Ministerials (the church, preaching, sacraments, etc.) which served this essential relationship with God and Incidentals (the different ways people do things); the Moravian Church’s encounter with the Protestant Reformation; the time when the Church lost its rights and went underground for 100 years; the rediscovery of the Moravian Church on the estate of Zinzendorf; the contribution of Count Nicholas von Zinzendorf; the changes after him and the modern period when the Moravian Church had to deal with new issues and became truly international. One interesting discovery of the last quarter century in North America is that Moravians really do have a theology, that their faith is not just simply living with Jesus though that still remains at its heart.

Nicholas Ludwig von Zinzendorf was a Count of the Holy Roman Empire. He was born in Saxony, educated at Halle and the University of Wittenberg as a lawyer, and studied theology on the side. His education and his position within society brought him (a Lutheran) into contact with different Protestant traditions, Roman Catholics and also Jews. He lived at a time which for some promised renewal of the church and yet raised many questions which seemed to undermine religious belief. This was the time of the Enlightenment, the birth of historical critical research and modern science which raised serious questions about traditional religious beliefs and affirmed human values, insights and possibilities. What was often left was a natural religion founded on reason of which the old religions were only cultural expressions. Zinzendorf read widely in the literature of the age and was appreciative of the issues raised and various efforts to address them. He formulated his own critical and creative responses which for us, three centuries later, seem quite relevant.

Zinzendorf’s religious life was very much affected not just by living in an “age of doubt” but by his own experience. His father died three months after he was born. His grandfather died when he was four. His mother soon remarried and managed his life from a distance. He was raised by his maternal grandmother, a well-educated woman who was acquainted with many of the European currents of religious reform and had a profound impact on his life.

At age eight, he was affected by arguments for atheism, and spent one long night in “meditation and deep speculation” about this, concluding that:

… because my heart is sincerely devoted to the Savior and many times I had wondered whether it were possible that there could be another God than he, - so - I would rather be damned with the Savior than be blessed with another God - so had speculation and rational deductions which returned to me again and again, no power with me other than to make me anxious and destroy my sleep. But in my heart they had not the least effect. What I believed, that I wanted; what I thought, that was odious to me.

Here was a discovery "that has stayed with me even to the present." Reason, the intellect, so useful in human matters for explaining and understanding, could not guide him in the resolution of religious questions. He resolved in spiritual matters to remain with "heart-grasped truth" and understood religious life as a living out of the companionship of the Savior.

His own personal journey of faith and the questioning of religious truths by reason and historical study, so much a part of the age in which he lived, caused him to take a particular approach to religion.

Religion is not about God or Christ or the Spirit, it is God and Christ and the Spirit. It consists of a living relationship with them. This can be described in different ways and expressed in different practices in different Christian churches, but the reality behind all descriptions is relationship with God. That is the central element, the Essential, which one needs to have in religion. This relational emphasis makes religion available to all who cannot form concepts but can share relationship, including infants – even in the mother’s womb. To express this relationship Zinzendorf chose various terms. Jesus’ relationship to the government of the church was expressed as “Chief Elder.” In personal relationships he was “Savior” and “Lord” or “Father of the household.” The Spirit was the “Mother” of the community and God was “Father.” From 1738 until Zinzendorf’s death the Mother role of the Spirit was much developed. When one accepts Christ one is accepted by the “Family” of God. Thus religion is so simple, though we often make it complicated.

Religion is known by the heart, rather than the head. The head represented the growing role of human judgment, reason and historical criticism, in examining religious truth. He argues that the head cannot figure it all out. The role and experience of the heart has nothing to do with emotionality or feeling. To know by the heart was regarded as objective perception, just as the five senses experience objective reality. “Heart” is a term for intuition or extra sensory perception. God has provided us with this other way of knowing what we cannot grasp by our intellect.

God made a decisive disclosure in history which would define what God is really like, necessary because there are so many possible understandings of religion from the human perspective. This was done in Jesus and that is why Jesus always needs to remain central. In one of his most famous poems Zinzendorf has God say to the poet who searches for God:

- Why, you foolish child,

will you fetch me from the depths?

Where do you think I can be found?

Do you seek me at heaven’s poles?

Do you seek me in the creature?

My nature, which no eye can see,

has built itself a body

and still you miss my sign. - O! Come here and see

the concealed Abyss,

the hidden Majesty.

In Jesus, the humble child, see

whether humanity exists in grace;

see whether He your praise deserves,

for whom love grows in the heart;

who believes, from all care becomes free.

To this the soul of the poet replies:

- O Eternity! Beauteous Light!

Reflection of the glorious King!

O love, which pierces heaven

to dwell in my small inn!

Here I discover, here I lay hold.

Of course I’ve not seen you,

yet one day that will be.

Now I love you, believe, and rest.

This disclosure makes it clear that God is one who joins us in life and shares with us the limitations and difficulties of human life, even to birth and suffering as a human. It is a rejection of the style of the God who dwells in heaven, on a throne, is always in control, and whose primary characteristic is pure power. And it makes clear that God comes to us as person and offers relationship. What is revealed is God, not about God. What is revealed is the God who dwells with us in the mystery and limitations of human existence.

In the New Testament Jesus is understood as God’s agent in creation. (John 1:1-18, Colossians 1:15-20 and Hebrews 1:1-3) His coming into the world is to complete what he started with us in the creation of the world and the creation of each of us. This means that every non-Christian religion also knows Jesus because they all know a Creator, though they do not have the clear definition of this Creator that can be found in the historical life of the Creator, in Jesus. Thus there is a bond of common experience with all religions, though definitions and understandings are not the same.

In addition, since Jesus is our Creator he knows each person born into the world and his work of salvation is to complete the process of our creation so that we fully become who we can become. Our Creator has always loved us and needs no persuasion to companion us in life. As he companions us he knows what we need to know when we need to know it, and he previously lived this life we live and so has great wisdom to share. Being companioned by him is also the basis for ethics.

Church is Gemeine (a community, fellowship), not primarily an institution or organization. The German term Gemeine (in modern German “Gemeinde,”) was the term which Zinzendorf most frequently employed for the Church. Hermann Plitt, author of three volumes on Zinzendorf’s theology, traces the development of this fellowship understanding of church from the Old Testament to the Savior’s Disciple-family, the early church, and then from the Church Fathers to the present. He argues that the nature of church is “spiritual, eternal, based on the community of life of its members with God and each other, in Jesus Christ, through faith and love, but its form is necessarily subjected to the changeability of human relationships, local and temporal conditions.” This was quite distinct from the term Religion which Zinzendorf uses to describe a religious tradition or institution such as Lutheran. Gemeine was used for the local congregation, the denomination, and the universal Christian Church, wherever persons lived in relationship with and from Christ and expressed the reality from which they lived. This term described a community which is a living organism, a system of spiritual reality, universal as well as local:

… I always make a great difference between a Gemeine and a Religion in genere [in kind]; and with respect to a Gemeine I am of the opinion that she stands in need of no new system because she is herself a daily system of God, a system which the Angels themselves study…

The church on earth and the church in heaven are both this Gemeine or “daily system of God.” The Moravian Hymnal of 1735 has on its title page a plate showing the earthly congregation on the floor level of the church and the heavenly congregation in the balcony. The two are never far apart. In each worship service they join one another. This is symbolized in the whiteness of the sanctuary and the use of clear glass to admit the light.

Each Christian Religion or denomination has within many persons who share this fellowship with Christ. Each Christian Religion also has its own “type” or “way” of teaching which contains many treasures. One should stay in the Christian Religion in which he or she belongs, but what ultimately matters is the common bond they share in Christ. For 50 years, until the last decade of the 18th century, the Moravian Church maintained the identity of three “ways” within it: Lutheran, Reformed, and Ancient Moravian.

Each book of Scripture is written within the context of its author and thus historically conditioned, something argued by the historical study of Scripture in his time. This is not just because each author is affected by his history and culture, but because God chooses to speak to us where we are. To each writer God has given what was necessary for his context, which is not the same as what God gave in another context to another person or community. God does not expect us to know everything, what is not necessary for us in our context. When one reads Scripture one then discovers the richness of God’s varied interaction with persons and cultures.

Two things are then necessary. The first is to recognize that Scripture is conditioned by history and context, and thus we have to learn to read it this way. But God has provided for the clarity of the Basic Truth necessary for salvation. Other materials, called Matters of Knowledge, need expertise to understand. And there are some things, such as what happens in the Lord’s Supper or what is to happen at the end of time, which will remain Mysteries, real but never to be fully understood. Christians need help to understand Scripture, to become established in Scripture. Thus he made two attempts to translate the New Testament, one with the books arranged in the order of their historical origin, and he started an abridged translation of the Old Testament, with less necessary and confusing parts eliminated.

Second, we have to know what or who we are looking for in Scripture. Certainly we can all look for Basic Truth and try to understand Matters of Knowledge, but Scripture is less about ideas than a Person. The Person of Christ is the real “system” of Scripture. It is about him and he is in it, reflected in it as in a mirror. If we can only meet him there we discover what (really Who) we need most.

Zinzendorf also encouraged the devotional use of Scripture. In 1731 he began the use of the Daily Texts which persons were to live with for each day, thus enabling them to use Scripture without worrying about how to understand a passage in its context. In the last years of his life he constructed a harmony of the stories of Jesus’ last days as a way to live into this important part of the story of Jesus.

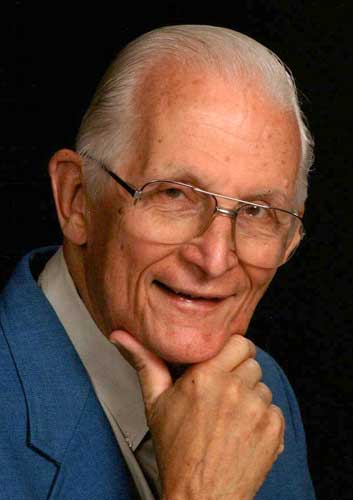

The Rt. Rev. Dr. Arthur J. Freeman (1927-2013) was professor of Biblical Theology at Moravian Theological Seminary in Bethlehem, PA. From 1974 to 1994, he was administrator of the Ecumenical Committee for Continuing Education housed at the Seminary. Dr. Freeman was ordained as a Bishop of the Moravian Church in 1990. Following his retirement, he continued to write and publish both texts and periodicals. He specialized in the theology of Zinzendorf, and published An Ecumenical Theology of the Heart: The Theology of Count Nicholas Ludwig von Zinzendorf,

Originally Published in Moravian History Magazine No. 18, ed. By J. and E. Cooper, Glengormley, Co. Antrim, N. Ireland. Used wuth permission of the author.

For additional information see:

John R. Weinlick, Count Zinzendorf, Abingdon, 1956, reprint Bethlehem and Winston-Salem: Moravian Church in America, 1989

Arthur J. Freeman, An Ecumenical Theology of the Heart: The Theology of Count Nicholas Ludwig von Zinzendorf, Bethlehem, PA, and Winston-Salem, NC: The Moravian Church in America, 1998.

Featured image shows a detail of the painting Zinzendorf als Lehrer der Völker des Erdkreises (“Zinzendorf as the Teacher of the Peoples of the World“) by Johann Valentin Haidt, circa 1747. Courtesy of the Moravian Archives, Herrnhut, Germany.

Published on December 30th, 2011