1741-1762

by Dr. Katherine Carté

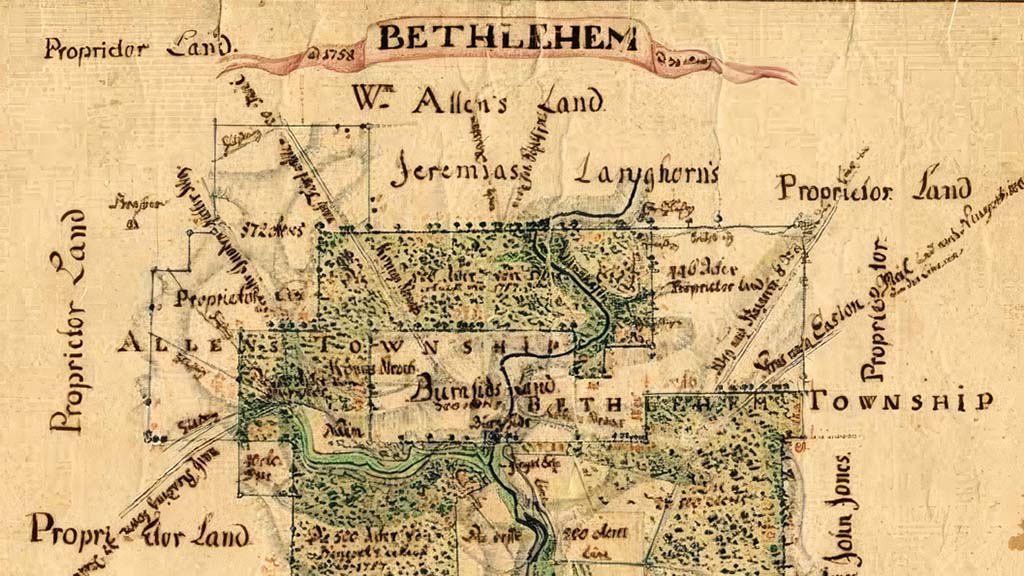

When the Moravians came to the “Forks of the Delaware” in eastern Pennsylvania, they quickly set about building a town that would become the center for Moravian missionaries and itinerant preachers in North America. A five hundred-acre tract located at the confluence of the Lehigh River and the Monocacy Creek offered the perfect location for their endeavor—fertile land near to white settlements and to the Indian lands to the west. The northern banks of the Lehigh sloped up gently, reminding the Moravians of the hill overlooking Herrnhut, in far-off Saxony. On the opposite side, a mountain separated the Lehigh Valley from Philadelphia, fifty-five miles to the south. The Monocacy Creek’s swiftly moving water provided them with the natural resources necessary for building in the wilderness. In 1741, during his yearlong sojourn to America, Count Zinzendorf celebrated Christmas in the new town, and formally bestowed on it the name of Bethlehem.

Although he never settled in America, Zinzendorf’s ideas were important for the town’s development. He believed the Moravians should support their preaching and missionary work through their own resources, rather than relying on payment from the communities and congregations they served. This would allow the Moravians to be seen as independent servants of the Savior, not slaves to the people they tried to help and teach. Financing such extensive projects was no easy task, however, for life on the frontier typically offered little room for luxuries or surplus production. To be profitable and to support its missionaries, the Moravians had to be efficiently organized. Bethlehem and the adjacent communities of Nazareth and the “upper places,” were organized into a single, communal unit, known as the Oeconomy—the Greek word for household. No one received wages for the work he or she performed. Instead, each person received hearty meals in the choir dining rooms, simple clothing, and shelter in the choir houses. Bethlehem housed the Moravians’ craft houses, such as the black smith shop and the tannery. Nazareth, where the land was better suited for farming, was the breadbasket for the settlers. Situated ten miles apart, these communities worked in harmony for the common purpose of supporting the Moravian evangelical and educational mission.

The Oeconomy endured for two decades. During this time, Bethlehem was the home of hundreds of Moravians and dozens of industries. A gristmill, a cobbler’s shop, a weaving house, and a dye house dotted the landscape. Carpenters worked with potters, smiths, and soap makers to provide for the needs of the Oeconomy’s residents and business services to non-Moravians who passed through Bethlehem or came there to shop. A steady stream of preachers, missionaries, and letters connected Bethlehem to their Indian, English and German neighbors, as well as other Moravian settlements around the world. Within Bethlehem and Nazareth, the Moravians lived dormitory-style, in choir groups constituted according to age, sex, and marital status. In most cases, even married people lived separately from each other, their children in the nursery or in children’s choirs. Bethlehm’s leaders dolled out jobs according to choirs as well—single sisters spun and washed, single brothers worked the fields, and married brethren were often employed in the craft houses. This system freed both men and women from family and domestic responsibilities so they could travel as preachers and religious teachers, while simultaneously staffing as many industries as possible, to finance the Unity’s projects.

Even during Bethlehem’s early days, some individuals were uncomfortable living in choirs rather than in traditional family households. In the late 1750s, the communal structure came under increasing pressure from both outside and inside Pennsylvania. The Unity’s rapid and ambitious expansion during the preceding decades had brought with it massive debts which were felt in all Moravian communities. In addition, the Seven Years’ War caused financial hardship in the Pennsylvania backcountry and in Saxony. Finally, Zinzendorf’s death in 1760 prompted a re-evaluation of the church’s economic organization. Bethlehem’s leaders had never intended the communal economic structure to be a permanent aspect of life for the Moravians in North America. In 1761, Bethlehem’s leaders set about the complicated process of shifting from one single communal household to a more traditional town made up of separate families. Not all communal ties were abandoned, however. The church continued to own all of the land in Bethlehem and Nazareth, and only Moravians were permitted to lease plots and build homes. The church also maintained control over several key industries, employing salaried craftsmen who worked for the benefit of the international church. The Single Brethren and Single Sisters’ choir houses continued to house unmarried or widowed adults.

Although Bethlehem’s communal period was a thing of the past by the time of the American Revolution, the Moravians’ distinctive, religiously oriented lifestyle lasted well into the nineteenth century. Architecturally, the Oeconomy period left a strong imprint on Bethlehem. The choir houses still stand on the hillside over the Monocacy creek today, offering visual proof of the town’s communal history. A unique period in Bethlehem’s history, the communal economy was never an end unto itself, but rather a means by which to support missionary and educational projects. Those projects lasted well beyond the end of the communal period, and in them can be seen the same religious spirit that inspired the Oeconomy.

For further information on Bethlehem’s communal period, see:

Faull, Katherine M. Moravian Women’s Memoirs: Their Related Lives, 1750-1820. Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press; 1997.

Gollin, Gillian Lindt. Moravians in Two Worlds: A Study of Changing Communities. New York: Columbia University Press; 1967.

Smaby, Beverly Prior. The Transformation of Moravian Bethlehem: From Communal Mission to Family Economy. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press; 1988.

Thorp, Daniel B. Chattel with A Soul: The Autobiography of a Moravian Slave. Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. 1988 Jul; 112(3):433-51.

Published on September 30th, 2011